Dan Bricklin's Web Site: www.bricklin.com

|

|

Turning Inspiration Into Our Own: May the Force Be With You . . . and You . . . and You

Works of fiction often serve as inspiration to innovators who then mold that vision in their own ways. What real people develop can improve upon the fanciful visions.

|

|

It is not uncommon to find an early experience that sets an inventor in a direction that leads to the "invention" of which we all take advantage. One of the reasons I included the entire transcript of the podcast interview with Ward Cunningham in Chapter 11 of my book Bricklin on Technology was to show the thread of influences that led to the elegantly simple tool of the wiki. In my own history (presented in the book and to some extent in the history section of this web site), you can see my early belief in the value of the computer as a tool for everyday people. To get to the spreadsheet, I started in the area of typesetting and word processing (stemming partially from being the son and grandson of printers and a newspaper editor) and then mixed in what I got from being formally exposed to the general needs of business (when studying for my MBA).

Sometimes the driving vision stems from the ideas of others, even from works of fiction. Helen Greiner is co-founder of iRobot, a producer of robots for the military as well as the home. As a child, she was inspired by the vision of robots like R2D2 in the initial 1977 Star Wars movie. R2D2 was just a facade, but Helen and her workmates brought the vision to life, with some robots autonomously cleaning living-room floors and others with human guidance defusing very real, deadly bombs.

There is another vision that I distinctly remember from that first Star Wars film. It is in the scene in which the Death Star has just destroyed a planet. The Jedi Knight played by Alec Guinness is suddenly distracted and seems ill. He says that he feels, ". . . a great disturbance in the Force, as if millions of voices cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced." This really struck me. Here, in a science-fiction film, with robots and fantastic weapons, was a strong spiritual metaphor: All living things were interconnected for good and for bad. It was their own voices that traveled, not a report from some observer distant from the event. It was so cosmic, personal, and all encompassing, trivializing the simple tools being shown on the screen at the time.

I don't know how many people this vision inspired, but an interconnection of the people of the world has nonetheless grown since then.

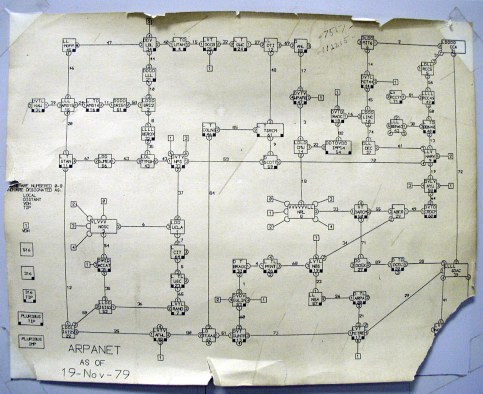

When we first saw that scene, the people of the world were very loosely connected. Few mobile phones, and no cell phones, were in public use. The ARPANET, the precursor to the Internet, was still pretty tiny. Here's a photo I took in 2002 at the Computer History Museum of a diagram of the state of the ARPANET in 1979 that shows how few systems were involved at the time:

ARPANET as of 19-Nov-79

When the planes struck the towers in New York City on Tuesday morning, September 11, 2001, most people found out the details by watching network television or visiting news web sites like CNN.com. A few had a more personal connection, as the New York Times observed:

Since cell-phone technology first came into common use in the past few years, there have been instances where someone trapped, nearing death, was able to call home and say goodbye. But there has been no instance like that on Tuesday, when so many doomed people called the most meaningful number they knew from wherever they happened to be and prayed that someone would pick up on the other end.

"The Call," New York Times, September 14, 2001

When the tsunami struck on December 26, 2004, the world was able to get some idea of how sudden and horrible it all was through the widespread dissemination on the Internet of amateur video. That sharing in a realization of what it was like surely helped spur some of the surge of support sent to the victims. The BBC pointed out the importance of the video and reports of everyday people in an article by Clark Boyd titled "Tsunami disaster spurs video blogs." Quoting professor Siva Vaidhyanathan, he wrote, "There was just no way to have enough professionals, in enough corners of the earth, on enough beaches, to have made sense of this."

To me, the idea that we were moving into the actualization of a fabric connecting humanity came at the beginning of the November 2008 attacks in Mumbai. I was checking my list of posts of people I follow on the Twitter "micro-blogging" web site. I saw reference to horrible things happening in Mumbai and a note that I could follow along by searching on the tag "#mumbai." I had a strange feeling reminiscent of other tragedies, but this time it came not through a call from a friend or relative but while participating in a world-wide conversation. Within seconds, I was seeing a flow of reports from people in the city, and information passed from person to person. As Charles Arthur wrote in the Guardian, "The effectiveness of the web showed itself once more with the terrorist attacks in Mumbai--with the photo-sharing site Flickr and the microblogging system Twitter both providing a kaleidoscope of what was going on within minutes of the attacks beginning."

Finally, in December 2008, my Twitter stream pointed me to a set of unusual "Tweets" from Mike Wilson, a person I did not know or follow on Twitter. As Robert Mackey later reported in the New York Times, after assuring that he was safely out of harm's way, Mr. Wilson sent out (typo included), "I wasbjust in a plane crash!" It was followed by very intimate, first-person accounts about the airplane that crashed during takeoff in Denver and how he was treated in the aftermath.

These are all stories of bad things happening to people. But, as I point out in my essay Learning From Accidents and a Terrorist Attack, since the bad times are so stressful on systems, we often learn a lot from bad situations that can help us in better ones.

The new interconnectedness in the real world is different from the vision in the movie. In the world we have been building, all can participate, not just a special few. That is how we are molding technology into a force with which we all can be creative and connect with what is really meaningful to us.

- Dan Bricklin, February 9, 2009

(This essay was originally written by Dan Bricklin for

the book Bricklin on Technology in early January 2009.)

You should also look at my essay (which appears well before this in the book): What will people pay for?

Two other interesting Twitter-related items:

Public Service of New Hampshire used Twitter to help communicate (in and out) with customers during the aftermath of a severe ice storm. Jon Udell interviewed PSNH's chief spokesperson Mike Murray who was in charge of that for ITConversations. You can read what Jon wrote on "A conversation with @psnh about the ice storm, social media, and customer service" and listen to the interview at "Social Media and Crisis Management" on ITConversations.

After the January 2009 Super Bowl, the New York Times posted a Flash app that let you look at a map of the USA and see dynamically the most popular words being used in Twitter postings (tweets) from various cities: "Twitter Chatter During the Super Bowl". It gives you a bird's-eye view of the conversations and the swing in emotions.

(By the way, you can follow me on Twitter as @DanB.)

-Dan Bricklin, February 9, 2009

See: A New Feeling at a Concert for an addition from a happier time.

-Dan Bricklin, May 6, 2009

|

|

|

© Copyright 1999-2018 by Daniel Bricklin

All Rights Reserved.

|